Open and Accurate Air Quality Monitors

We design professional, accurate and long-lasting air quality monitors that are open-source and open-hardware so that you have full control on how you want to use the monitor.

Learn MoreLast month, Achim attended the CLEAN-Air Forum 2025 in Nairobi, Kenya, where policymakers, global experts, community groups, and individuals came together to showcase their clean air solutions. Although I wasn’t there in person, I was still able to connect with some of the exhibitors through his introduction – one of them being the team behind APAD, or Air Pollution Asset-Level Detection.

Ahead of our conversation, I read up a bit on APAD’s work and learned that much of their focus has been on identifying and mapping pollution sources such as brick kilns – industrial ovens that produce building materials but also release large amounts of smoke and particulate matter.

To understand how this initial focus has since grown into the broader project it is today, I spoke with APAD’s communications lead, Jaisha, who walked me through their approach, how it all started, and where the project is headed now.

APAD began in 2024 with the support of an Innovation Award from the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at the University of Oxford. Their mission is a powerful one: make air pollution sources visible, measurable, and actionable using citizen power, data, and storytelling.

The team behind APAD has created one of the first open-access pollution asset datasets, which now includes over 70,000 mapped pollution sources across more than eight categories. One of their biggest milestones was building Pakistan’s first open-source brick kiln database, a major step toward addressing a significant source of emissions in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP).

This emphasis on open access reflects a broader motivation that has guided the team from the start: bridging the gap between academia, industry, and policy-making by ensuring that the collected data is made accessible for everyone.

To make this possible, APAD combines advanced technology with detailed analysis. Using machine learning and deep learning models, they processed more than 1.2 million satellite images to identify visual signs of pollution, such as brick kilns or field burning.

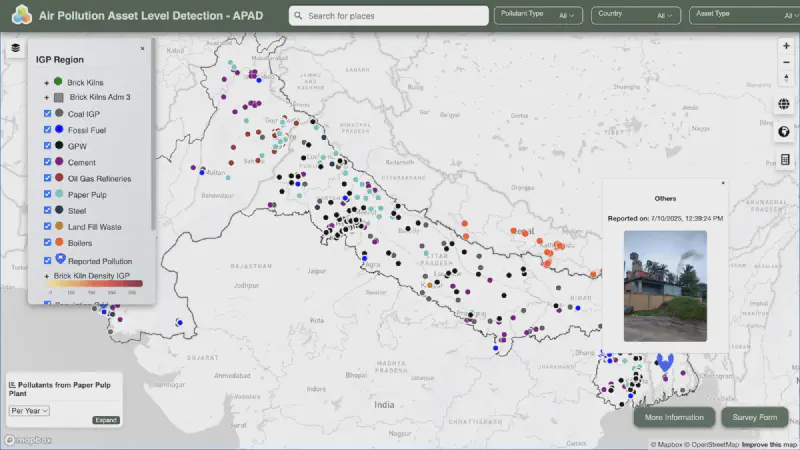

The process starts by training the model to detect brick kilns as primary sources of pollutants. The model was taught to recognize different kiln shapes – rectangular and oval – and to distinguish them from other structures. Once the system detects likely kilns, it groups them into clusters called “signal masses” and determines their central coordinates, or centroids, before geolocating and mapping them. Building on this, the team employs transfer learning to locate and geo-tag other pollutant sources.

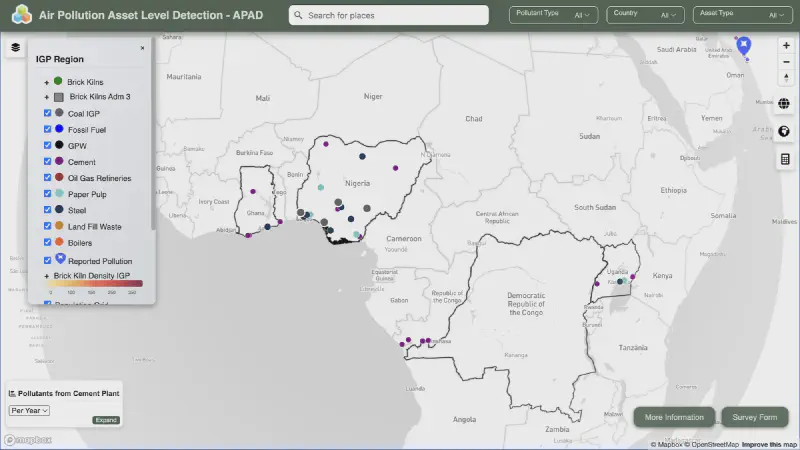

These findings are then added to APAD’s open-access map, where anyone can explore the data and see how pollution sources intersect with nearby communities, schools, hospitals, and the environment.

While these methods could be applied anywhere, APAD chose to begin in the Indo-Gangetic Plain – a region facing some of the world’s worst pollution, and also where the team is based. Severe air quality challenges and limited, inaccessible data made it a necessary starting point. Their work has since expanded into parts of Africa, where similar problems persist.

By concentrating efforts in regions with both high pollution and data gaps, APAD is able to create datasets that are urgent and capable of influencing meaningful interventions.

As effective and advanced as these methods are, the APAD team also wanted to create something that would address the “citizen power” aspect of their mission. This led to the development of the APAD app, a platform where community members themselves can directly contribute data.

Through the app, people can record localized sources of pollution that satellites might miss, such as burning trash piles, open sewers, or illegal kilns. Recently, this data was integrated into the map with its own distinct pin design. If you click on one, you can see information such as the date of the report, as well as a photo of the pollution source submitted by the user. This combination of satellite findings with citizen reports helps bridge the gap between large-scale monitoring and the lived experiences of those who face pollution daily.

As for what lies ahead, Jaisha shared that the app had only just launched a week before the Nairobi conference, and within that short time, the responses have already been encouraging. Downloads climbed quickly, and the team began receiving valuable feedback from new users eager to be part of the effort.

To build on this momentum, the team has also recently launched a volunteer program, where individuals from the IGP region and parts of Africa such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and Uganda, can become part of a network that can help with on-ground pollution reporting, community outreach, and research. If you are based in any of these areas and would like to be a part of this growing community, you can sign up to be a volunteer here.

The citizen science phase of APAD is still new, but that’s exactly what makes it exciting. It has opened the door for communities to be active participants in environmental monitoring, rather than passive recipients of information.

By combining open data, advanced technology, and communities on the ground, APAD is showing that clean air is a shared goal that we can all help make real.

We design professional, accurate and long-lasting air quality monitors that are open-source and open-hardware so that you have full control on how you want to use the monitor.

Learn MoreCurious about upcoming webinars, company updates, and the latest air quality trends? Sign up for our weekly newsletter and get the inside scoop delivered straight to your inbox.

Join our Newsletter