Open and Accurate Air Quality Monitors

We design professional, accurate and long-lasting air quality monitors that are open-source and open-hardware so that you have full control on how you want to use the monitor.

Learn MoreThis article is part of a series, where we explore the hidden complexities of PM2.5 — tiny airborne particles that impact air quality and health. We will uncover the ambiguities behind its measurement, the challenges in assessing health risks, and the surprising insights that emerge. Each article will tackle a different aspect of PM2.5, shedding light on its hidden dilemmas and unanswered questions. Today’s article discusses the variety of different airborne particles.

Ever wondered how airborne particles look like? I mean yes, we cannot see them by the naked eye, but still, they must look like something. To figure this out, we can collect airborne particles on a filter and then simply look at them through a microscope. This sounds straight-forward, but it is not. Why? Only very small particles defy gravity and remain airborne for a long time. While they are small enough to be deposited in the lungs when we breathe, they are often too small for microscopes.

Let’s think of a PM2.5 particle with a diameter of 0.3 micrometers, which is unbelievably small. I mean it is way smaller than a bacterium. How crazy is that? This website is great to get a feeling for the scale. Go and try! It allows you to zoom in until you find the E. Coli bacterium which is around 1 micrometer.

0.3 micrometers are even smaller than the wavelength of light, which demonstrates the problem: how should we see something that is smaller than light itself? It is impossible. Such a particle is simply too small for an optical microscope, regardless of how good it is.

Luckily, a hundred years ago, scientists came up with a genius idea: they developed microscopes which do not use light. Instead, they use electrons, which are much smaller than light and thus allow much higher resolution. I believe the development of the electron microscope is one of the most important contributions within science. It was honored with a Nobel prize.

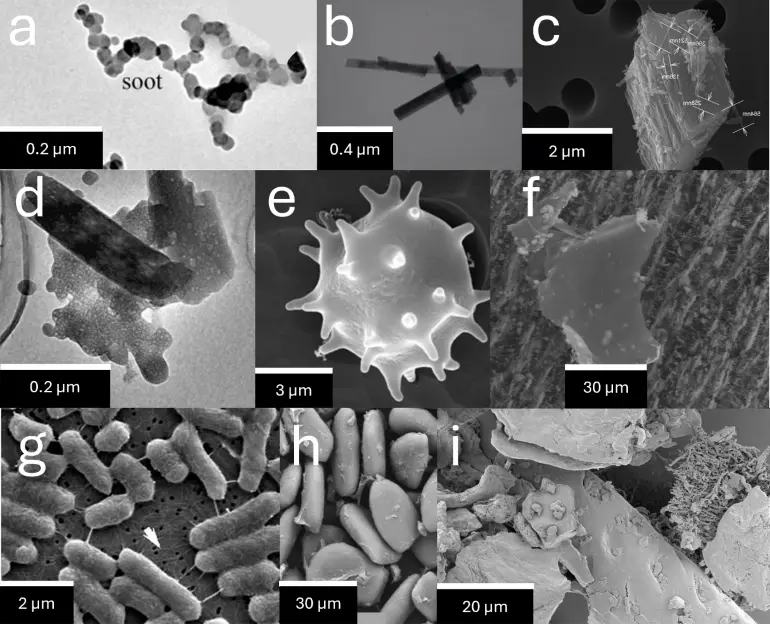

Equipped with electron microscopy, scientists could then take pictures of very small things, such as airborne particles. I have compiled a collection of pictures of different particles (see Figure 1). It shows the diversity of airborne particles, both in terms of shape and size.

Figures 1a-f show particles that were collected from air, while Figures 1g-i provide non-airborne examples to put the size of airborne particles into scale. In the English language, airborne particles are often referred to as particulate matter smaller than 2.5 or 10 micrometers, abbreviated with PM2.5 or PM10. In German language, however, there is the word ‘Feinstaub’ to describe airborne particles. It translates to ‘fine dust’ and emphasises a critical aspect: ‘fine dust’ is not just dust. Instead, it is orders of magnitude smaller. Please note that house dust in Figure 1i looks massive compared to PM2.5. Due to the difference in size, PM2.5 enters our lungs, while house dust is deposited in our nose, where it eventually gets slowly excreted as boogers.

Figure 1a shows soot, which is formed during combustion of carbon. It is arguably the airborne particle that has caused the highest health damage to the human species. It is emitted where carbon burns: wildfires, cigarettes, combustion engines, gas stoves, coal burning etc.

How does soot form? Carbon is converted into CO2 when exposed to high temperatures and oxygen. However, before conversion to CO2, some of the carbon can accumulate in the air to chemically form bigger carbon molecules. The quantity and size of these gaseous carbon molecules increase if less oxygen is present. At some point, these molecules can get so big that they solidify and become airborne nanoparticles, known as soot. The soot nanoparticles further collide with each other, giving rise to the typical soot agglomerates shown in Figure 1a. Note that these processes take place within a very short amount of time during combustion.

The agglomerate in Figure 1a is roughly 0.5 micrometers long, while individual soot nanoparticles seem to have a width of approximately 0.02 micrometers based on the picture. Note that 0.02 micrometers equal 20 nanometers, which is roughly as long as a chain of 200 hydrogen atoms. This is mindblowing and emphasises that we approach the atomic level of matter when we talk about particles of this size.

Why is soot toxic? Generally, having dust in our lungs is a bad thing. The body tries to get rid of it and triggers a cascade of defense mechanisms that may lead to chronic inflammation, eventually promoting lung diseases. Unfortunately, soot is small enough to reach the deepest part of the lungs and it often carries carcinogenic molecules, which can cause lung cancer.

All particles above have one thing in common: they are solid. However, in real world, there are also liquid or partly liquid PM2.5 particles. Electron microscopy is biased in this sense as it unintentionally eliminates many liquid particles. Why? Electrons inside the microscope collide with air molecules, which causes awful picture quality. To avoid that, the air within these microscopes is sucked out with really powerful pumps, eventually causing low ambient pressures of 0.00001 Bar and below. Many volatile components like liquids evaporate under these conditions and cannot be seen anymore. An exception are cryogenic electron microscopes that operate at super low temperatures of below -100 °C, but these instruments are normally not used to study PM2.5. In summary: the microscope changes the composition of the sample and may raise the impression that all analysed particles were solid. Note that many airborne particles are not solid, for example cloud or fog droplets. It is not entirely clear what PM is emitted by cooking, but it can be assumed that there is an oily liquid fraction, for example when stir-frying.

Airborne particles come in various states, shapes, and sizes as seen in Figure 1. They often consist of completely different materials, ranging from salt in sea spray to carbon in soot. The size determines how long the particles remain airborne and how deep they can reach into our lungs. Given this large variety of particles, it seems obvious that different particles differ greatly in health effects. For example, airborne sea salt raises less concerns than soot. The former may dissolve within our lungs, unlike the latter which accumulates and poses a health burden.

Does the PM2.5 standard accurately capture this diversity of different particles? No, it does not.

Is it still useful to know the total mass of PM2.5 in the air? Yes, it is but we should be aware of the great diversity of particle shapes, sizes and materials when it comes to ways of measuring PM2.5 concentrations and understanding PM2.5’s health effects.

The following articles in this series will dive deeper into the real-world implications if people ignore this variety.

Curious about upcoming webinars, company updates, and the latest air quality trends? Sign up for our weekly newsletter and get the inside scoop delivered straight to your inbox.

Join our Newsletter

We design professional, accurate and long-lasting air quality monitors that are open-source and open-hardware so that you have full control on how you want to use the monitor.

Learn More