Open and Accurate Air Quality Monitors

We design professional, accurate and long-lasting air quality monitors that are open-source and open-hardware so that you have full control on how you want to use the monitor.

Learn MoreEvery year, the World Health Organization (WHO) sits down with its 194 member states to decide what matters most for global health. It’s a huge negotiation; cancer, outbreaks, vaccines, maternal care, climate, nutrition; everything is on the table. Evidently, the budget is finite and tradeoffs are inevitable, as investments into one health domain mean less funds for the others. So, how are these priorities set, and who decides?

For the current 2024-2025 cycle, WHO’s total budget is around US$ 6.8 billion. This is spread across three main pillars, reflecting the organization’s core strategic priorities:

In theory, countries tell WHO what they need most, and WHO builds its agenda around this. In practice, however, what matters most is who is paying, and for what.

WHO’s funding comes from two main streams:

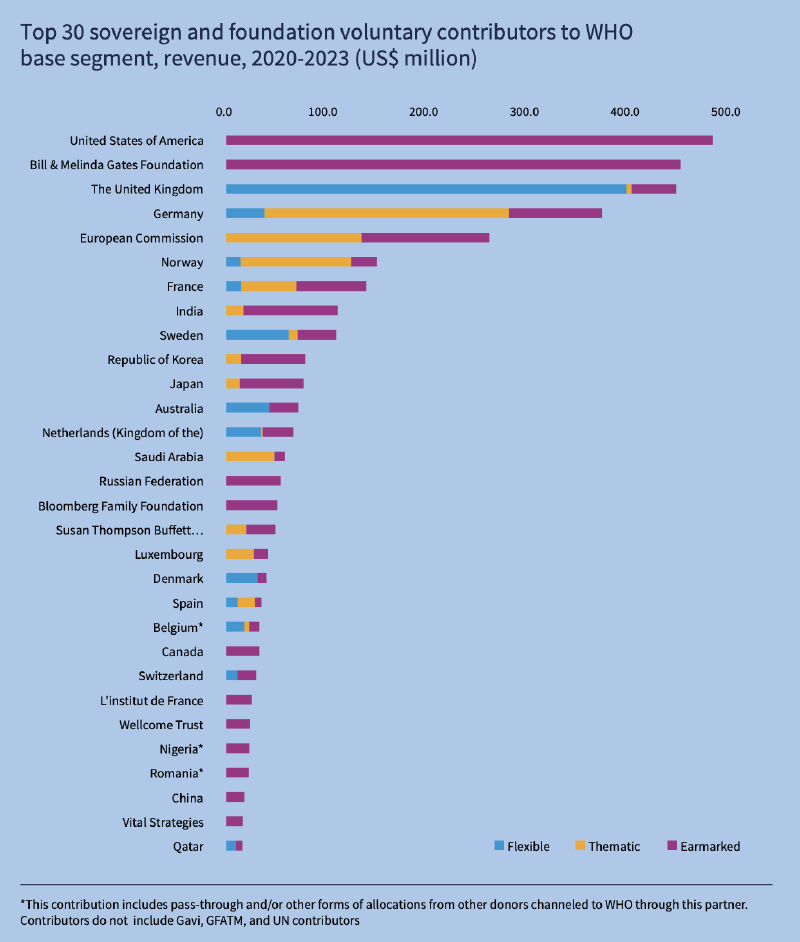

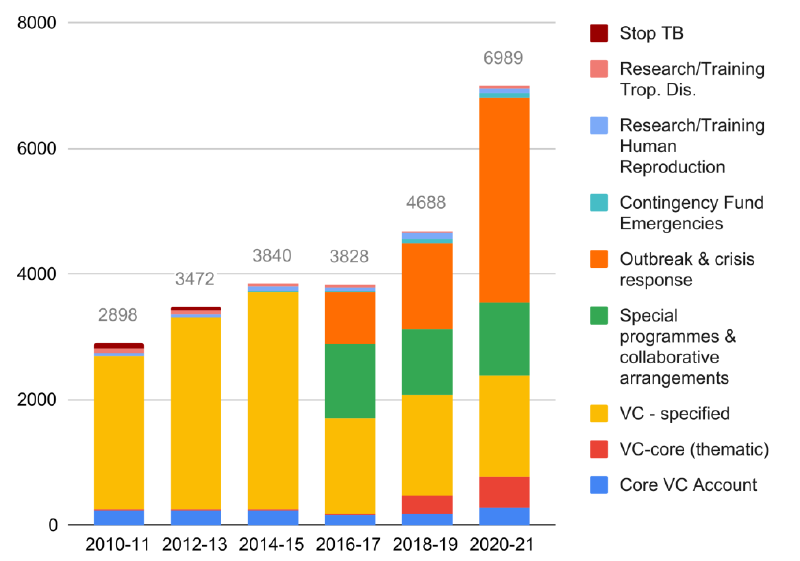

Voluntary contributions come from member states, private organisations, or philanthropies, and are for the most part earmarked. Voluntary earmarked contributions made up 60% of WHO’s budget in 2024, a figure which has increased over time. This trend has raised concerns of diversion from WHO’s strategic priorities; reliance on these earmarked funds creates a situation where external donors dictate the organization’s priorities and action agenda.

As a result, the organization has limited room to manoeuvre. Due to the conditionality of these funds, it can’t divert them from well-funded programmes like polio eradication towards other projects, such as building air quality monitoring networks in polluted cities.

The 2024-25 programme budget has allocated funds to be distributed as follows:

This follows a similar budget allocation to previous years, where the third pillar is consistently the least funded. And even so – this pillar covers a wide range of categories, with air quality interventions representing only a very small share. The approved programme budget for 2024-2025 for the Healthy environments sub-category, which is the most relevant for air quality, is US$ 168.8 million – equivalent to about 2.5% of the total budget. There is no exact figure for how much of this funding goes into air quality projects specifically, however, it can be estimated that it represents less than 2.5%. Furthermore, it must be emphasized that this refers to the approved programme budget set out by WHO, which does not accurately reflect where spending actually ends up due to the high share of earmarked funds.

Beyond WHO, air quality is globally underfunded. According to the Clean Air Fund, only about 1% of global development funding goes toward financing outdoor air quality solutions, even though air pollution causes over 7 million deaths per year – this is more than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined.

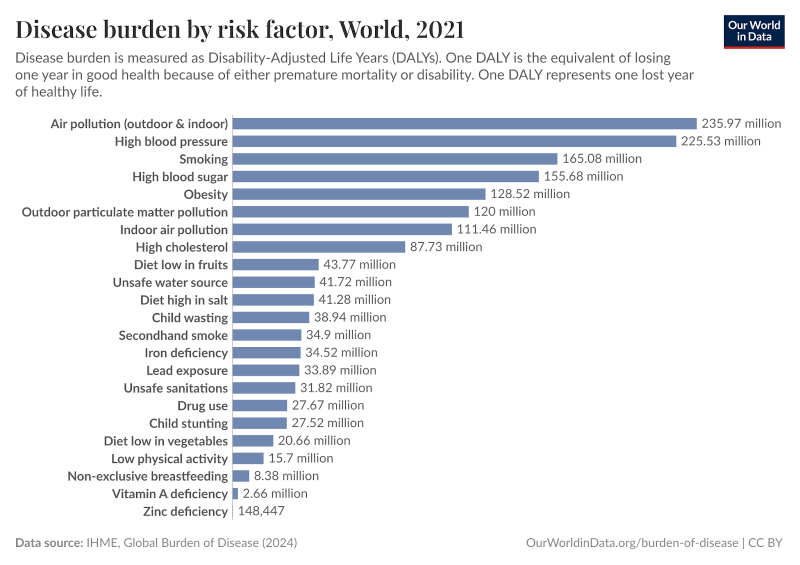

Air pollution ranked as the top risk factor of disease burden in 2021, with urban outdoor air pollution consistently ranking within the top ten risk factors and as the first environmental risk factor in high-income countries. In low-and middle-income countries, the ranking remains high, with women and children bearing the greatest health impacts from the use of polluting fuels and technologies in households.

In addition to its importance as a global health issue, air quality interventions have been proven to work, with a high return on investment (ROI). Every dollar invested in air pollution control returns up to US$ 30 through saved lives, reduced healthcare costs, and higher productivity.

In the graph below, we can see that there is a high discrepancy between the high disease burden of air pollution and the funding that goes towards combatting it, despite the high ROI. We could expect that health issues with higher funding have a higher burden of disease – however, relative to air pollution, this is not the case.

So why does clean air stay underfunded?

One reason may be because it doesn’t fit easily into donor boxes. Air quality is messy – it touches energy, transport, industry, agriculture, housing, which are all outside traditional “health sector” lanes. It’s difficult to locate air quality interventions in WHO’s own data, seeing as they intersect numerous categories such as environmental health and NCD prevention.

Political optics also have their role to play. In a context where thousands of health domains and projects are battling for placement on the WHO agenda, those with faster, more visible outcomes may be prioritised by member states. Eradicating an infectious disease, for example, has a clear finish line that is more easily discernible by the electorate, making it politically attractive. Clean air takes cross-ministry cooperation and years of work to tackle, and can never be fully achieved but rather continuously improved. Donors will therefore prefer quick wins with tangible results.

The transboundary nature of air pollution also makes it a “wicked problem” requiring international cooperation, and in its absence, efforts can be rendered futile. One country’s progress may be offset by its neighbor’s higher pollution, which further weakens the incentive to act.

As seen by the data above, WHO is largely reliant on conditional funds targeting priorities set by member states and third-party themselves. Therefore, even if air quality was to climb the ranks of WHO’s priority list, it wouldn’t automatically lead to a significant increase in investment.

In 2024, WHO tried something new. It launched its first Investment Round, a global fundraising drive with the aim of expanding its donor base and generating more flexible and predictable funding. The goal is to raise US$ 7.1 billion in voluntary contributions for The Fourteenth General Programme of Work (GPW 14), which is estimated to save 40 million lives in 2025–2028.

It’s important to note that current investments focusing on the first two pillars aren’t a loss; with the rising burden of NCDs and the increasingly rapid spread of infectious diseases, any funding towards better health is valuable. However, the impact of this funding can vary. Countries should consider elevating environmental health in their own priority-setting so that it doesn’t get drowned out by short-term crises. And for donors, it’s time to realise that clean air isn’t just an environmental issue; it’s one of the smartest health investments money can buy.

References

Clean Air Fund. (2023). The state of global air quality funding 2023. https://www.cleanairfund.org/wp-content/uploads/The-State-of-Global-Air-Quality-Funding-2023-Clean-Air-Fund.pdf

Clean Air Fund. (2024). The state of global air quality funding 2024. https://s40026.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/State-of-Global-Air-Quality-Funding-2024-UPDATED.pdf

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2024). Disease burden by risk factor (processed by Our World in Data). https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/disease-burden-by-risk-factor

Iwunna, O., Kennedy, J., & Harmer, A. (2023). Flexibly funding WHO? An analysis of its donors’ voluntary contributions. BMJ Global Health, 8(4), e011232. https://gh.bmj.com/content/8/4/e011232

Jha, P. (2025, November 14). COP air pollution report: Clean air monitoring investment offers high return. Semafor. https://www.semafor.com/article/11/14/2025/cop-air-pollution-report-clean-air-monitoring-investment-offers-high-return

Reddy, S. K., Mazhar, S., & Lencucha, R. (2018). The financial sustainability of the World Health Organization and the political economy of global health governance: A review of funding proposals. Globalization and Health, 14, 119. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186/s12992-018-0436-8.pdf

World Health Organization. (2023). Financing WHO: Report by the Secretariat (A76/4). https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/pb-website/a76_4-en.pdf?sfvrsn=648fd79f_7

World Health Organization. (2023). Seventy‑sixth World Health Assembly: Resolution on financing (A76_R1). https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA76/A76_R1-en.pdf

World Health Organization. (2024). All for Health, Health for All: Investment case 2025–2028 (ISBN 9789240095403). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240095403

World Health Organization. (2024). Investment round: Frequently asked questions. https://www.who.int/about/funding/invest-in-who/investment-round/frequently-asked-questions

World Health Organization. (2024). WHO launches its first Investment Round to sustainably finance its Health for All mandate. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-05-2024-who-launches-its-first-investment-round-to-sustainably-finance-its-health-for-all-mandate

World Health Organization. (2025). Financing and implementation of the Programme budget 2024–2025. Report by the Director‑General (EB156/26 Rev.1). https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB156/B156_26Rev1-en.pdf

World Health Organization. (2025). Financing and implementation of the programme budget 2024–2025: Report by the Director‑General (WHA78/19). https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA78/A78_19-en.pdf

World Health Organization. (2025). New data: Noncommunicable diseases cause 1.8 million avoidable deaths and cost US$ 514 billion every year, reveals new WHO/Europe report. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/27-06-2025-new-data–noncommunicable-diseases-cause-1-8-million-avoidable-deaths-and-cost-us-514-billion-USD-every-year–reveals-new-who-europe-report

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Air pollution: Burden of disease attributed to air pollution. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/2259

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Our work: Core priorities. https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/core-priorities

We design professional, accurate and long-lasting air quality monitors that are open-source and open-hardware so that you have full control on how you want to use the monitor.

Learn MoreCurious about upcoming webinars, company updates, and the latest air quality trends? Sign up for our weekly newsletter and get the inside scoop delivered straight to your inbox.

Join our Newsletter